Former and current top BLS and BEA officials publish paper

Difficulties in adjusting to the digital economy and globalization have led to a chronic overstatement of inflation and, in turn, an understatement of real GDP. That's according to five current and former BLS and BEA researchers.

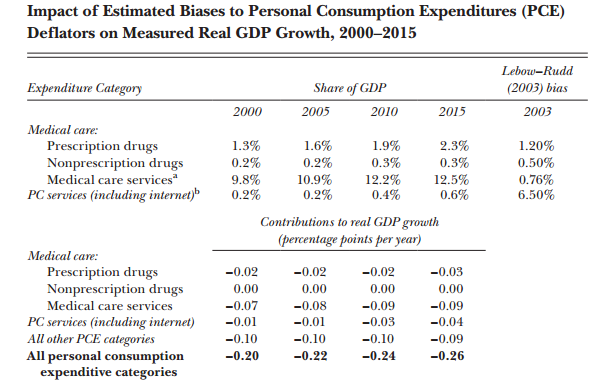

"Based on our analysis of bias estimates performed by experts external to the Bureau of Labor Statistics and the Bureau of Economic Analysis, we find that these influences on existing price indexes may overstate inflation in the categories of 'personal consumption expenditures' and 'private fixed investment,' leading to a corresponding understatement of real economic growth of less than one-half percentage point per year," they write.

The paper wades into the thorny issues about how to adjust prices to technological change. In addition, it touches on trade with a thinly-veiled reference to how iPhones are produced.

"In a globalized economy, many goods are US-designed (an investment) but manufactured abroad. This practice creates particular problems in accounting for the domestic value of intellectual property. For example, consider a smartphone that is designed in the United States, produced in an Asian country, and then purchased and imported by the US firm for final sale. The Bureau of Economic Analysis counts the wholesale value of the phone, which may include the value of the US firm's intellectual property, as an import and in final sales. Ideally, BEA would also capture the export of the intellectual property to the foreign producer on its surveys of international trade in services. However, under certain contract manufacturing arrangements, there may be no separate transaction for exports of design/software to the Asian manufacturer, thus understating exports in the national accounts," they report.

The paper was published earlier in the month but is getting some attention today.

It's almost taboo to talk about how difficult -- if no impossible -- it is to get good economic data. Dozens of assumptions and adjustments go into every report and it undermines monetary policy, if not financial markets.

An adjustment error of 0.2 percentage points per year in four separate years seems small but it's compounded over time.

In any case, the paper is a great primer on the challenges and assumptions that go into economic data.

Better yet, rather than appointing a dozen officials to the FOMC who are slavishly dedicated to the data; they could help to balance the discussion by adding an experienced BLS or BEA statistician.