Or more accurately, the inability of investors to hedge US dollar risk

From Deutsche Bank makes a great point on what could drive the dollar higher:

A remarkable hunt for yield has taken place over the last few years. Foreigners have fled negative rates and flocked to US fixed income to take advantage of positive rates. Currency hedging these purchases has been a popular strategy: investors buy long-end bonds and use short-dated forwards to eliminate the FX risk.

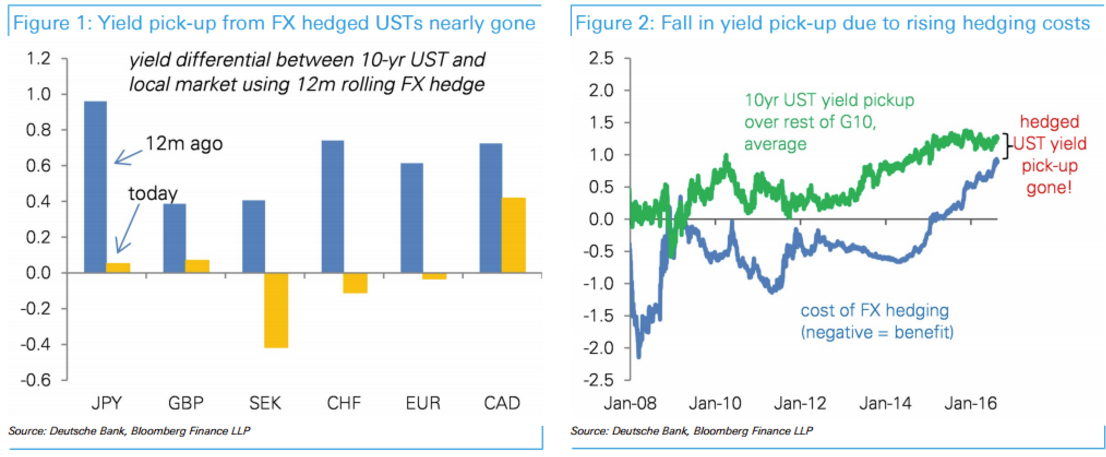

Yet something significant has happened in recent months: buying 10-yr US treasuries is no longer profitable. It is not only Europeans or Japanese, there now isn't any global fixed income investor that can make decent money by buying hedged USTs (chart 1).

Even more remarkably, the reason behind this lack of return isn't that long-end yields have compressed: the rate differential between the US and the rest of the world has stayed quite stable. Instead, it is diverging central bank policy (Fed hike vs cuts elsewhere) and the widening in crosscurrency basis that now makes it very costly for investors to hedge (chart 2).

We draw a number of conclusions from these simple observations.

First, it is hard to see the relentless foreign buying of hedged US fixed income continuing at the same pace. Unless other bond yields decline deep into negative territory (they are already zero), there may be limits to how much more UST yields can compress.

Second, the rise in forward costs is bullish USD. If investors want to pick up AAA yield, they will have to do so unhedged, which will generate demand for dollars. If they don't want FX risk, investors will have to buy higher-yielding corporate bonds or other riskier US assets.

To connect the dots further, the guys over at Zerohedge write about how the same problem (rising short-term US dollar costs) are putting a squeeze on Japanese banks who need to roll over somewhere between $125-$150 billion in short-term funding.

The difference is that some Japanese firms might opt out of the US market altogether rather than hedging.

"Being increasingly locked out of money markets means that beyond paying up subsantially for U.S. dollars, Japanese banks have few options. Leverage requirements mean global banks are reluctant to provide repos, while foreign-exchange swaps would be a more expensive way to access U.S. dollar funding, said Koichi Sugisaki, a rates strategist at Morgan Stanley MUFG Securities. Three-month CP and CDs now cost roughly 80bp-90bp on an annual basis, but three-month FX forwards have also become more expensive at around 1.5 percent per year, he said.

So the question is whether they will pay up for dollars, hold the Treasury risk or keep their money at home? How that question is answered is huge for what happens next for USD.

Another alternative is to issue short-term US dollar-denominated debt but so far that hasn't been tested in Japan.

In the bigger picture, what happens in funding markets is far more critical than what the Fed does but there is a risk that a hawkish Fed turns a problem into a crisis.