Lessons from past Federal Reserve tightening cycles

Since Ben Bernanke’s warning this week that QE will “taper”, markets have taken fright. The S&P500 lost 3.5% from highs Wednesday to close on Friday, while the German DAX lost 5% and the UK’s FTSE 3.7%. Continuing an on-going trend, emerging markets lost more, with The Hang Seng down almost 6% before some recovery on Friday. Bond markets have already had a bad month in May and the rate on the benchmark ten-year US Treasury is now up to 2.5% — the highest since mid-2011.

Yet none of what Ben Bernanke said should be a surprise. There have been murmurings from the Fed about the approaching end to QE since the beginning of the year at least. And clearly interest rates cannot stay low forever. With a strengthening economy, the “ZIRP Experiment” will end and the “Great Normalisation” will begin.

So why have markets reacted as they have? Firstly because talk is not the same as reality. And secondly, when everyone is having a party, no one wants to be the early to leave in case they miss the fun. Fixed income has had one hell of a party – an eighteenth, twenty-first, stag, hen, wedding and divorce party combined. Its been a 30-year bond bull market party and as most of us have experienced, the longer the binge, the more painful the hangover.

So what can history teach us about the morning after?

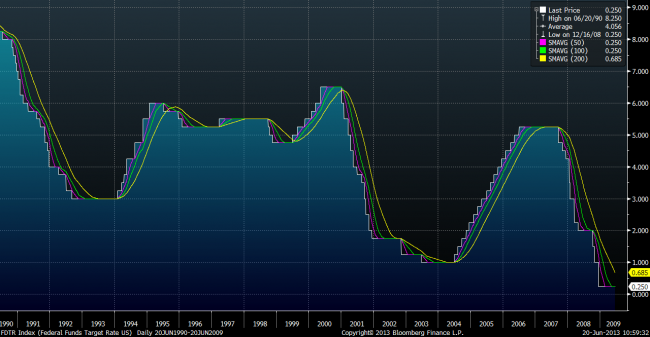

There have been two periods during the past 25 years when the Fed has tightened considerably – 1994 and 2004. What can we learn from them?

In 1994 Ace of Base occupied three top ten positions in the US Billboard charts and that`s still my favourite.

I was 24 and two years into my life at Goldman but the Fed almost cost me my career. Investment banks were taken by surprise by the Fed’s tightening, suffered huge losses in their fixed income divisions and by the end of the year, staff were being let go. Orange County, California was the naked swimmer that got caught when the tide receded and went bust after it lost $1.7bn from debt and derivatives (but it wasn’t the only one).

On February 4,1994 the Fed increased its key rate by 0.25% to 3.25%. Markets were spooked and the Dow Jones fell almost 2.5% on the day. The tightening continued and by the middle of 1995, eighteen months later, the Fed Funds rate finally doubled to 6.00%. The scale of tightening was unexpected as according to one newspaper report from the time, only modest rate rises were predicted – 3.5% by end 1994. What is interesting is that after the initial shock, the stock market didn’t really move – the S&P was about flat for 1994. The big move though was in long term interest rates – 10 year Treasuries yields increased from 5.75% to 8% that.

But as soon as investors sniffed an end to the rate increases, the stock market started to rise and the 10-year yield fell back again by the end of the next year – 1995. Inflation had been controlled thanks to rate increases and that was good for bonds; growth was strong and that was good for equities.

Fed funds rate

So what about the experience in 2004? The Fed tightened Fed Funds rate from 1.00% to 5.00% in 2006. During this period the US stock market was pretty strong – the S&P500 started 2004 at about 1100 and ended 2006 at almost 1300, a rise of around 20%. What is interesting is that the long term interest rates were much less affected by the Fed. The yield on ten-year Treasuries, albeit a bit volatile, was effectively flat at 4.5% over the period.

The first thing these examples show us is that equities do not have to fall as rates increase. In fact they can rise as higher rates are the monetary response to a stronger economy. Secondly it teaches us that the effects on the yield curve – the term structure of interest rates – can be very different. In 1994, the ten-year bonds collapsed, but in 2004-06, ten-year yields were essentially unchanged.

There is a major difference in 2013 – QE. It down down ten-year US Treasury yields as low as 1.4%, way below the levels of 1994 (5.75%) and 2004 (4.5%). Secondly by pulling all rates of return down, it has forced investors who would normally prefer the relative safety of bonds into equities. Many believe this has “artificially” inflated stock prices – it is visible that stock markets are pushed higher after QE.

10 year yield history

So although 1994 and 2004 show that Fed tightening need not be catastrophic for either bond or stock markets, this time it’s different. We do not face an “ordinary” tightening cycle because the monetary stimulus has been exceptionally large.

However the phrase “this time its different” always makes me nervous as it tends not to be true. So let’s look at the differences between ‘94 / ’04 and now.

- Firstly the Federal Reserve is much more transparent about policy than it has been in the past. It realises it must handle the adjustment to more normal rates exceedingly carefully. This means bond markets are much less likely to be spooked and surprised as we saw 1994.

- Secondly, equities are not that expensive and companies have spent the years of the crisis restructuring, taking costs our and loading up on cheap debt. Thus corporate earnings growth from a recovering economy should be strong.

- Thirdly and this is a bit of a technical / mathematical argument, but any bonds issued in the last five years will have lower coupon payments than those issued in the 1990s and 2000s. Prices of low coupon bonds are super sensitive to interest rates moves. So when interest rates increase as we know they will, all these bonds issued in the last 5-7 years will fall a lot more than the higher coupon bonds of in 1994 and 2004.

I was reminded of the super sensitivity of low coupon bonds to interest rate risk by an FT piece written by an M&G bond vigilante. And this highlights another thing to remember when reading people’s opinions. They talk their own book. No bond fund manager is going to tell you how bad its going to be as they will be talking themselves out of a job. The call to sell bonds may as well be a call to “Fire Me”. To explain that the bond sell off will be a lot worse this time around because of low coupon bonds but still end up bullish is explained by the fact he is running the bond fund business! Also most bond fund managers, traders, sales people and brokers have only experienced one type of market – one that always goes up. And this never ending decades old bull market has taught them that every set back has been a long term buying opportunity. That is dangerous.

Along the same lines, I looked up all the CEOs of investment banks to determine their backgrounds. The last person you want running an investment bank at the moment is someone from a fixed Income-only-ever-a-bull-market-buy-at-every-opportunity CEO. Thanks to the financial crisis, fines, bankruptcy and scandal, most CEOs have been replaced with corporate banking, wealth management types. However the one exception is Goldman Sachs whose CEO, Lloyd Blankfein came from a commodities and fixed income trading background. Ex-colleagues tell me the firm has been taken over by the Bond Boys. Clearly money equals power and the money has mostly been made in the fixed income, currency and commodities business for many years. Someone who is only ever used to a buy at every opportunity market is not ready for the reverse.

So my opinion? Bond markets will be crushed when rates go up and normalise. After a 30 year bull market, and rates now so low, it is a mathematical certainty. But equities might be able to continue to perform if the earnings growth is good. Yes, equities are valued against bonds – there is a relationship between dividend and bond yields. But remember dividends are not fixed, like bonds, they increase with profits.

I started with a song from 1994, so let’s end with one from 2004.

To be brutally honest I am not that keen on many of Billboard hits from that year, but this is a good one.

There shouldn’t be a correlation between great years of pop and the US bond market although it wouldn’t surprise me if a hedge fund supposed alpha seeker found one. Data mining throws up all sorts of weird nonsensical relationships. Given that the predicative capabilities of most economists and strategists are dire, maybe forecasting the bond market using musical taste could be a way forward…

So then you need to decide in 2013 is a great musical year like `94 or not so great like ’04.

Thoughts please….