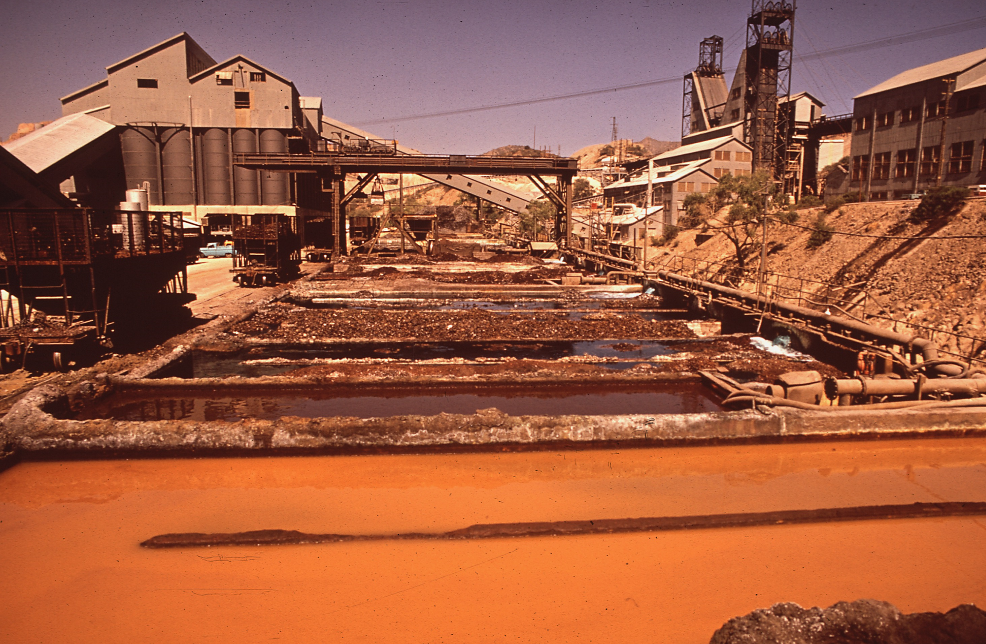

Copper is an example for how a bust ends

Commodities analysts expect to see a bottom in oil and metals when someone starts cutting production. That's when balance (and calm) should return to markets.

That's not what is happening in the copper market. The lesson is that in a rout, supply and demand matter less than market psychology.

The anatomy of a commodity boom and bust

Copper was at the front end of the commodity bust.

It first began to fall as emerging market demand unwound and continued to decline as a Chinese invoicing scam unwound.

Like other commodities, there was massive overproduction. In the oil market, that continues because producers don't want to give up yet even if they're unprofitable. They believe that if their rivals quit, prices will rebound and they can continue.

Eventually, someone throws in the towel.

That's supposed to be when the market bottoms

What's going on in the copper market

Some copper producers threw in the towel more than a year ago. Upwards of 600,000 metric tons of copper supply has been taken out of the market over the past 12 months, according to Morgan Stanley, about 3% of production. About 20% of Chilean copper mines are idled.

Meanwhile, Chinese demand has been strong. Despite the ubiquitous chatter, demand was up 26% year-over-year in December, according to China customs data (which, admittedly, might not be the most reliable source).

What it says about other commodities

Copper is an indication of how long the commodity bust may continue and how it might fall far below what 'anyone' is expecting.

This week, copper continued to carve out fresh post-crisis lows. It's a sign of damaged market psychology. As a trader it argues for selling any bounce in oil or other commodities when companies finally crack and cut production.